By Jennifer Skillen, Gordon Rugg and Sue Gerrard

Some diagnoses are clear and simple, and give you a crisp either/or categorisation; either the case in question has a positive diagnosis, or it doesn’t. Diagnosis involves identification of the cause of a problem; this may occur in medicine, or in mechanical fault finding, or in other fields. This article focuses on medicine, but the concepts involved are relevant to diagnosis in other fields.

The diagram below shows crisp either/or diagnosis visually; cases either go in box A or box B, with no other options.

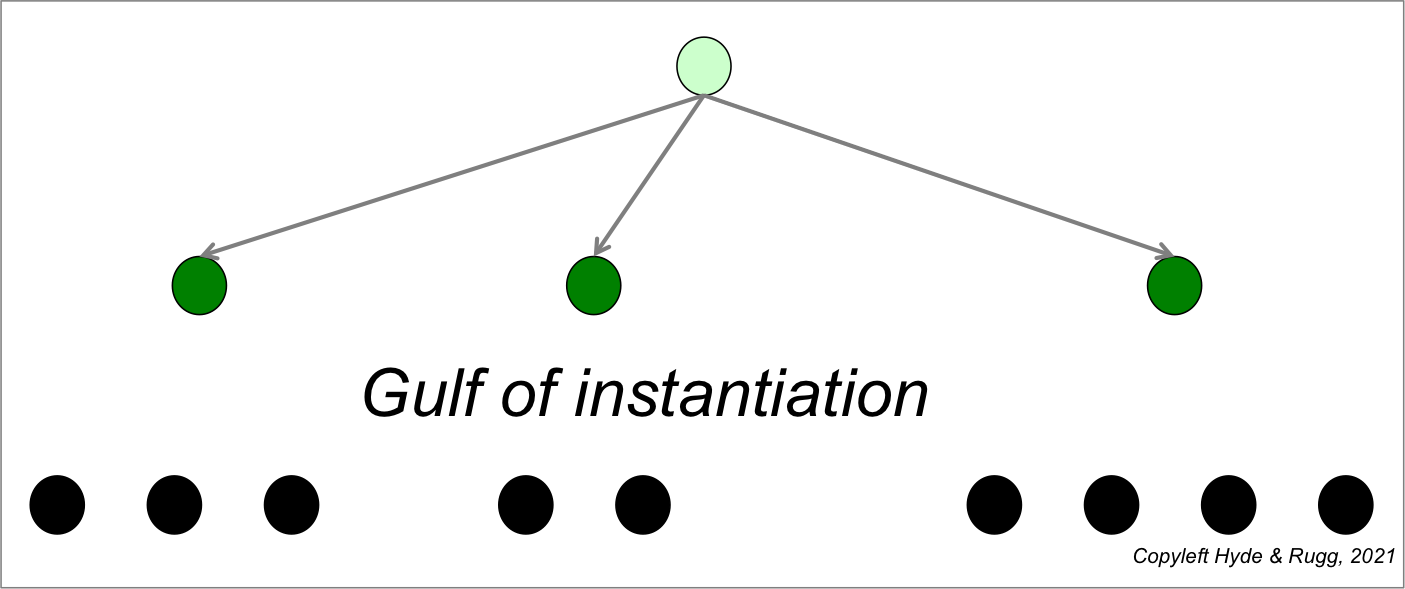

Not all diagnoses are this simple. Medical syndromes are an example. A syndrome in the medical sense involves a pattern of features that tend to co-occur, but where the cause is unknown. They typically involve multiple signs and symptoms, each of which may or may not be present in a particular case. (Signs are features that can be observed by someone other than the patient; symptoms can only be observed by the patient.) Making sense of syndromes, and of how to diagnose syndromes, is difficult, and often encounters problems with misunderstandings and miscommunications.

This article discusses ways of defining syndromes and related issues. Its main focus is on medical diagnosis, but the same principles apply to problems in other fields that have the same underlying deep structure.

Continue reading